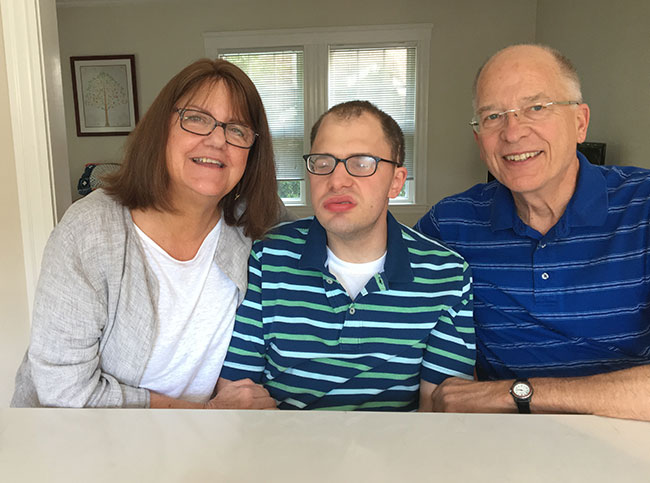

Our 29-year-old son, Christian, was born prematurely after his heart stopped beating. His brain did not receive oxygen for 12 minutes and he suffered brain damage similar to a significant stroke. He’s had hundreds of hospitalizations and 80 surgeries, including 40 neurosurgeries. He has cerebral palsy and is visually impaired. He has significant difficulty communicating, knowing what he wants to say but not being able to say it. In spite of all this, he is still his own person.

Christian now lives at The Guild’s Sudbury House and is thriving. He has a big heart and a great sense of humor. He loves to be active and engaged. He uses technology well and enjoys TV, computers, iPads, etc. He knows what he wants and likes.

Of course, every child, family and experience is different, but these are some of the lessons that we learned as we parented our son:

Find an expert that you trust

Raising a child with disabilities and serious medical problems required knowledge and skills that we did not have. We tried to become experts but the learning curve was steep. Along the way, we met talented providers who were clearly experts. They were willing to tell us the truth, and we trusted their experience. We learned to do what they said, even when it was not what we were hoping to hear.

Christian’s vision for life

As Christian approached his 22nd birthday, we asked an expert how we could begin the process of finding adult services. We had a long list of what we wanted and sought advice about how to find it. We were told to throw away the list and write a vision statement for Christian that he would write if he could. We realized that our priorities were not his priorities and that his preferences needed to be respected.

Getting along with other people

Christian was always a smart kid (relatively speaking). When he was about 10, he joined the class of a very wise teacher at the Perkins School for the Blind. We proudly told her about his academic strengths. She knew that Christian had great difficulty expressing himself and that it was often the cause of behavioral problems. She politely said, “None of that matters if he can’t communicate or get along with others.” She was right. The ability to communicate his needs and interact well with others are the most critical skills for Christian to have.

Friends can’t understand but can help

We were sometimes frustrated that our lifelong friends struggled to understand what our family was experiencing, and the difficulty they had adjusting their lives to accommodate our family’s needs. We didn’t always see how sincerely they wanted to help. Friends can’t change the struggles and disappointments, but they can love and support. We learned to ask for help and to accept their kindness, however it was offered.

Functional goals are most important

Functional skills are most important in adult services. Even the slightest improvement will impact quality of life. Goals for toileting; dressing; feeding; expressing hunger, thirst and pain; waiting for others; and coping with frustration were not always Individual Education Plan priorities in childhood, but they are essential for life as an adult with disabilities. School time spent on functional rather than academic goals is time well spent.

He will have a meaningful life

We still sometimes feel sad that Christian will not have the life that we dreamed of for him. He will not have a partner who loves him. He will always struggle to communicate. He will not always have his parents to love and support him. However, we have learned that there are many kind and caring people who will protect him and support him the best that they can. And, much of the time, Christian will have what he needs. Christian will have a life that feels meaningful to him.